Three gunmen attacked the editorial offices of the French satire magazine Charlie Hebdo on Wednesday. When they left, 12 were dead and 11 injured. In the days since, at least five more have died: four hostages and a police officer. Two of the Charlie Hebdo suspects — two brothers with links to jihadist groups — and a third jihadist have been killed in shoot-outs with police.

I deplore the act and grieve for the victims, but I am not Charlie.

It’s not because I can’t imagine being targeted because of what I do or where I work. When I worked for the Martha’s Vineyard Times, we gathered like clockwork every Thursday morning to critique the issue just published and start planning for next week’s edition. Any passerby could see us through the office’s big front window. If someone had chosen to take violent exception to one of us, to something in the paper, or to the paper itself, we would have been sitting ducks.

Of course no one ever did. It wasn’t all that uncommon for an aggrieved reader to storm in, berate one of the editors or reporters for something that had or hadn’t appeared in the paper, and then storm out again. But no one ever came in shooting or tossed a bomb or booby-trapped a car in the parking lot.

The possibility never crossed our minds.

Celebrating Lammas’s anniversary, ca. 1984. From left: owner-manager Mary Farmer, yours truly, and Tina Lunson, the community’s favorite printer.

Before I moved to Martha’s Vineyard, I worked at Lammas, D.C.’s feminist bookstore. Lammas was a highly visible center of the feminist, lesbian, and gay communities. We were quite aware of the rhetoric directed against feminists, lesbians, and gay men. There was some risk involved in being so publicly, visibly “out” in an easy-to-find place. We did it anyway.

Across the country and around the world men and women were taking similar risks for similar reasons: staffing bookstores, publishing books, editing magazines and newspapers, producing concerts, making record albums, hosting radio shows, all to make visible and audible the voices that the mainstream media weren’t interested in.

To listen to the mainstream media now, you’d think that the US of A was a veritable hotbed of free and unfettered speech. Ha ha ha. As A. J. Liebling famously said long ago, “freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” The same is true of the other much-ballyhooed U.S. freedoms. This is what we were doing with our bookstores and publications and record companies: fighting for our freedoms.

Je ne suis pas Charlie, mais j’étais off our backs.

As a college junior, in the fall of 1971, I spent more than a week in Lawrence County, Mississippi, as a poll watcher for Charles Evers, the first black candidate to run for statewide office in Mississippi since Reconstruction. We poll watchers, both black and white, were potential targets. We knew it. Sometimes we were uneasy, and a couple of times I was downright scared.

But after the election we got to go back to being college students in Washington, D.C. The Mississippians who hosted us, fed us, trained us, and worked with us remained behind, visible, vulnerable — and working for justice. Day in, day out, they were risking their lives, safety, and livelihoods for the right to vote and the right to have someone worthwhile to vote for. They were some of the bravest people I’ve ever met.

The terrorists in those days were white Christians. This may be why the mainstream media doesn’t call them terrorists.

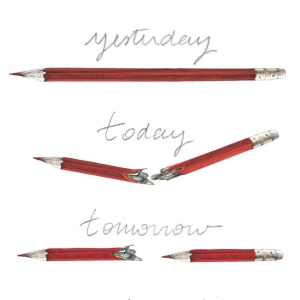

Image attributed to Lucille Clerc

It’s a platitude among the privileged that “the pen is mightier than the sword.” In a widely circulated image, apparently by illustrator Lucille Clerc, the pen is a red pencil.

At first glance the image unsettled me. The sharpened fragment looked like a missile chasing the other fragment. It made me think of impending rape. The analytical side of my brain got the point, so to speak. The artist was not thinking of missiles or rape, but there it is.

The pen, or the pencil, may be mightier than the sword, but only if the words and images created with it are heard and seen in the wider world. If the words and images are dissed or ignored, or if they remain in the creator’s head, they don’t have much power at all. Back in the day we created bookstores and publications and distribution networks to get our words out. It was hard work. We did it because we hoped and had faith that it would make a difference.

Lacking that hope, that faith, that belief, and seeing that the pens and pencils are often pointed at us — well, the sword might look like a better option.

Reblogged this on Write Through It and commented:

This is from my other blog, but it’s about writing. Oh yeah, it’s definitely about writing.

LikeLike

I always appreciate your opinion on many issues. What I think is lacking after the current events that happened in France is history. Although I support (and always will) freedom of speech, I am fully aware that what happened was brewing and is the consequences of political decisions, of unfair distribution of wealth in the world, of the huge role weapons of war play in our economies, of immigration failure, among the most important reasons. I will always condemn acts of terror, but it would be stupid to pretend that nobody bears some kind of responsability. I read Charlie Hebdo when I was a student in France. Back then everyone wasn’t a Charlie. In fact, the magazine didn’t do wo well. Thank you for another honest, informative, based on facts, post, Susan.

LikeLike